This is an edited version of the letter I read to the Board of Canadian Art in August 2020, amended to include the role of Hyperallergic.

When I joined Canadian Art, I had just started my Masters degree, I was in my mid twenties, and naively optimistic about the change I thought I could make within one of Canada’s most established art institutions. I knew during my second month into my position as Indigenous Editor-at-Large that I wanted to work towards a different career outcome, and a job at another organization, after being yelled at by Debra Rother, then Publisher, and David Balzer, then Editor-in-Chief, in front of the entire staff. When I say yell, I don’t mean spoke sternly. I mean, she raised her voice and made a point of humiliating me in front of the entire office, which was (and remains) open concept. My offence was that I was being harassed by a powerful man for citing an Indigenous woman who had confronted him regarding the claims of misconduct that had been swirling around him for years in my online article “Making Space in Indigenous Art for Bull Dykes and Gender Weirdos.” A report has since been released, following an inquiry, that confirms those claims.

Months before the #MeToo movement exploded online, I brought Canadian Art a complex and considerate response to misogyny in Indigenous creative communities. As a result, a man referenced in the article threatened to sue me and the publication. This is what led to Rother and Balzer yelling at me in the office, though I had asked for us to take the meeting in private. Based on behaviours throughout our work together, I have no doubt the pair were making an example of me. The next day Rother, alongside the board of the magazine at the time (I assume), had devised a legal document that was handed to me by Balzer to sign. I was told I must approve the redaction of the reference, without any consultation or input from myself or the affected communities.

Before the morning I was asked to sign this document, I had been up all night struggling with suicidal ideation because of the pressure being put on me by the man in question and the public. My partner drove to Toronto from Montreal, where we lived, in the middle of the night because he believed I was a risk to myself. It felt like Canadian Art only cared about its reputation and the safety of the organization, at the expense of my mental and physical safety. Today, I cannot believe how naive I was to sign that paper without question and without a lawyer present. I did not know that this was the magazine shifting liability to me, their part-time, contract employee, to save the philanthropic and white governing class of the organization (in essence, at the expense of my defamation). I did not know that the redaction would then be used to undermine victims and to discredit my career and work among my colleagues. To this organization, I was something to be controlled. But I was also not disposable because I represented a steady stream of reconciliation income from private and public funding bodies. During my time at Canadian Art, I was dissuaded from writing for other publications, though I was intensely censored and my work was often scrutinized at Rother’s request following the aforementioned interaction.

During my time at Canadian Art, I was a part-time employee. I was never a full-time employee at Canadian Art despite, many times, working full-time hours, often in instances of short staffing. This happened frequently because the magazine has one of the highest turnover rates of any organization I have ever worked for. I was paid for 20 hours a week, but worked full-time hours for the majority of my contract. I made under $2000 per month. Two editors were hired to fill my role when I left.

My position was always made (and devised) epistemologically separate and disposable to the organization. I would try to negotiate or gain more clarity on these hours from my Publisher and Editor-in-Chief, including asking for a title change to reflect that I was working harder than some full-time employees with higher titles and pay and asking for a full-time salary twice. Each time I was denied or derailed, while I watched other employees have their hours increased and new positions be developed.

During my time at Canadian Art, my position was utilized in a variety of ways to bolster the reputation of the organization and publication. For the launch of the “Kinship” issue, the organizational side of Canadian Art instigated a series of escalating conflicts with the Banff Centre, using my position as leverage to attempt to organize a issue launch there that the centre had never consented to (and firmly kept stating they did not want to hold at the centre, at that). The organization put pressure on Banff Centre that relied heavily on mobilizing my position and Indigenous identity politics, and even asked me to call in favours with various Indigenous contacts to make this happen.

Here, I think masculinism and an analysis how art often operates through a politics of posturing power and importance is important. I remember puffed chests and big egos in the office around this time; and promises of millions more in funding based on my position and the Indigenous representation in Canadian Art (but without my consultation or involvement). My job and job security was always leveraged in these big, private funding asks during this time.

Canadian Art also let me know I was obliged to go to the Banff Center during the “Indigenous Art Journal” residency, to promote “Kinship,” though I had actually asked for time off because of escalating conflict between the organization and Indigenous artists that was then projected on me based on my connection to the organization. This is another of my darkest periods, filled with suicidal ideation, as I attempted to keep my head above the conflict and hurt, thousands of miles away from my home and family, having been refused the time off I desperately needed. “Just one last push,” I was told. It was always just one last push.

Despite pay and employment inequities, Canadian Art made a habit of pushing me out into community to be the face of the organization, often at the expense of my own health and wellbeing, and though the organization was in consistent conflict with Indigenous communities regarding the politics and actions of the organization. Often I would be promised additional pay for doing extra gigs and travel. Seldom did these honorariums materialize. Though I was made the smiling brown face of the organization in public, I was completely disempowered to address instances like the Archer Pechawis misprint publicly, or to be a part of the process of how those deeply offensive errors would be dealt with institutionally.

The “Spacetime” issue, from its inception, was devised as a counter ploy to beat the Inuit Art Quarterly and be the official publication at the Venice biennial that ISUMA curated. Yet, during the previous bienniel, the organization had gotten support to attend and only white management attended on our behalf. This happened on many occasions: the inability to socially integrate Indigenous employees into the fabric of the institution, though our identities were leveraged as a selling point for the magazine. While Indigenous content ruled the pages of Canadian Art, it was not Indigenous employees who were reaping the benefits of that work.

During my time at the magazine, we would consistently get feedback from Indigenous interests about insensitive content in our magazine, and the Publisher and Editor-in-Chief never responded to those critiques. Yet, the organization often had the time to email back and forth regarding content with white philanthropic interests. The organization was never accountable to the communities it leveraged to to boost its funding.

During the conflict at Open Space, Canadian Art moved forward with an event during an organizational pause at the artist run centre. During this time, Canadian Art used me as a shield with the Indigenous community and utilized me to perform tasks of emotional labour. An individual on the organizational side even got me involved with a personal conflict that resulted from these interactions, that ended up involving our Editor-in-Chief, again with no consultation from me regarding the final outcome of this conflict. The result was the deterioration of my personal and working relationships with several artists of colour.

On the day-to-day, Canadian Art was, without a doubt, a “toxic” workplace. At the beginning of my position, a member on the organizational side of the magazine sent a series of my tweets around the office, ridiculing me and inferring I was not representing the organization well. To be frank, it all felt very high school. What followed was a tactical project of gossip and bullying by white staff members who surveilled me and treated me as Other. In collaboration with other employees of colour, I have developed the opinion that this moment can be connected to a series of harassing behaviours waged by white employees against the growing number of employees of colour on staff. I remember feeling so utterly alone. I do not have a trust fund or rich parents who can bail me out, like so many individuals who have the time and resources to participate in art do. I couldn’t just quit. This was my job and a job I needed. But I also learned early on that working at Canadian Art meant gearing up for the weeks I was there being filled with conflict and toxic cultures among the staff.

I did send an email to the staff at the time of the above event asking that, if there were issues in the future, they confront me as opposed to sending emails discussing me without my consent or without approaching me first. The Editor-in-Chief took me for coffee and said, and I quote, “Young BIPOC come into organizations and are always calling people out but they don’t ever want to do anything about it. You just need to try harder.” I left the conversation shocked and wondered why I was the one being penalized for confronting that I was being harassed in the workplace. It is not lost on me that these emails came from someone who was a friend to Balzer outside of the office. It is also not lost on me that those making full-time salaries in the organization, but not doing full-time work, consistently pushing their tasks on Black and Indigenous employees, were close friends of Balzer. Balzer’s inner circle was always safe in a way that Black and Indigenous employees were not during his tenure at the magazine.

My work in online publishing, my work on the “Kinship issue,” and other work by editors of colour defined Canadian Art at a time when it had no identity. We brought Canadian Art a readership they were never able to access previously. We are what defined its reputation in a current era of Canadian publishing, after the publication almost folded because it couldn’t pull itself out of its status as tired trade magazine made to serve its funders – largely white arts administrators. Yet, during this time, white employees with lesser education and experience in publishing would fly past me and other editors of colour to get promoted into high level positions within the organization. White colleagues on the administrative side would get raises and title changes to reflect their work, and senior editors who negotiate new titles to ensure their own authority within the hierarchy. It would seem that there was either preferential treatment of white employees, especially in hires, on the organization side; or it was far too lucrative for the organization to keep me pigeonholed into an identity-stake role connected to reconciliation funding. As my successes grew and my work was recognized, Balzer’s animosity and cruelty only increased. In several instances, afraid to speak to me about my content, Balzer mobilized other members of editorial to take me to task for my work, creating deep rifts among editorial for an extended time.

In grants that were eventually shared with the staff, my position was one of the most publicized to drum up diversity funding, though I was always the lowest paid on staff. As recently as July 2020, I have correspondence from Rother confirming that she was discussing my position with Canada Council as a positive for Canadian Art and as leverage for further funding conversations, despite that I had been quietly planning an exit strategy from the organization for years.

I never imagined I would have to say these things publicly. I am a good Cree kid. If you give me a chance and I have called you a mentor, I will hold that space for you for an eternity. I probably would have protected Balzer for the rest of my life based on my respect of the fact that he took a great risk to hire me, an up and coming writer with some big ideas. What did force this response is that, despite signing a confidentiality agreement, David Balzer broke the trust and silence he promised to maintain to protect the peoples he employed.

Before giving weight to Balzer’s article that erases the actual work by Black and a Indigenous employees to intervene on Canadian Art, notably his own misconduct as Editor-in-Chief and Co-Publisher, I want to be clear that the structures of exploitation at Canadian Art noted above were completely devised by Balzer. The grants were written by Balzer. The toxic cultures emanated from Balzer and his mis-management of staff.

Yet, in July 2020, Balzer published an article in Hyperallergic framing himself as a lone martyr, without complicity, in what occurred at Canadian Art. In doing so, he referenced, without consent, the employees of colour he had exploited and treated so poorly. Two men of colour, Hyperallergic’s Editor-in-Chief and critic Seph Rodney, acted as commissioners and editors on this article. The employees referenced in the article were trans folks and women of colour, who were all employees of Balzer at the time the offending occurrences happened.

I contacted the Editor-in-Chief of Hyperallergic letting him know the above. I asked whether or not the article had been fact checked because much of the information within the article is highly susceptible to legal inference. I also asked about the board structure of Hyperallergic. I asked about ethics in publishing and how a magazine could publish, without question, an article wherein an outgoing editor references Black and Indigenous employees non-consensually, especially given it was his own deplorable actions that (partially) resulted in him being asked to step away from Canadian Art. I should be careful here. Balzer was not asked to step down because of racism but because of his inability to truly grow into the role of manager and Editor (partially, his continued perpetuation of a toxic working culture among editorial and inability to facilitate cohesion within the organization). The publication of his article contributed to his continued human rights violations in the workplace; and, ethically speaking, as an editor and a professional in publishing, an article about human rights violations against Indigenous and Black peoples by the person who actually committed the acts is questionable at best. I did find some irony to see that Balzer signed an open letter calling out the Banff Centre for unethical treatment of its staff, given all of the above.

Upon reaching out on social media, I was blocked by the Editor-in-Chief of Hyperallergic. My subsequent emails were not answered. I also sent an email to Hyperallergic editor Elisa Wouk AlminoI, who did not respond. This, in itself, is pretty sketchy publishing protocol, and especially considering that Hyperallergic is a publication that prides itself on being a voice of accountability in the arts.

Considering the previous Indigenous art content published on Hyperallergic, and their quick and steady ramp up of Indigenous art content following my contacting them regarding this issue, I will assume that Hyperallergic does not have any Indigenous representation in its organizational or editorial community; nor are its members versed in the politics of Indigenous sovereignty and whose land they occupy.

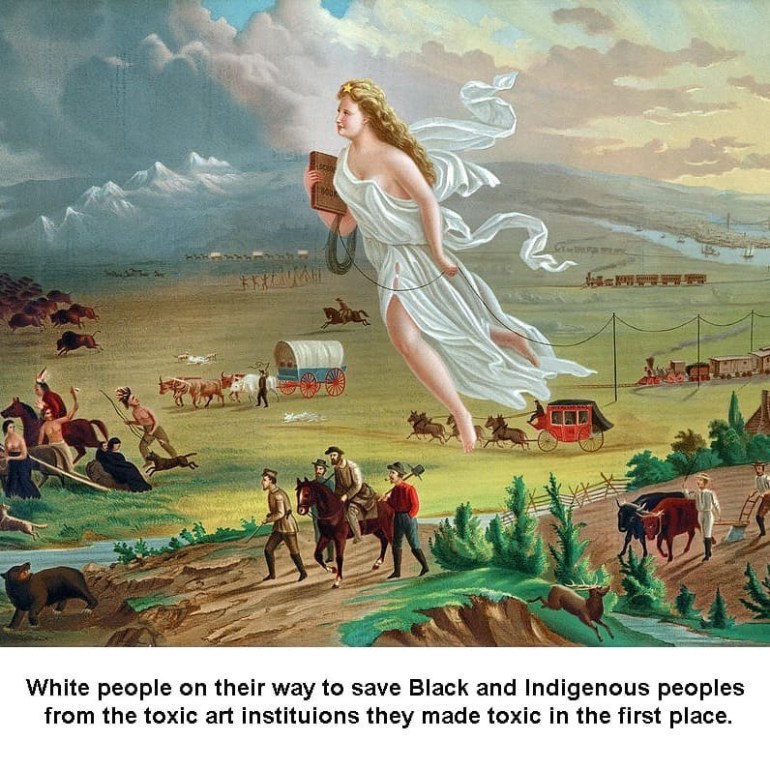

The actions of Hyperallergic have shown the limitations of performative discourse in the arts and recent institutional conflicts have inspired my perception of the hallow and apolitical work that can happen in publishing. For instance, the podcast Reply All recently began airing a series calling out toxic workplace cultures at Conde Nast, but was swiftly publicly addressed by former employees of colour for secretly harbouring its own anti-Black and toxic workplace cultures. Instead of looking inwards or being accountable to their publication of this article, Hyperallergic has shown its internal structure to be deeply masculinist at a governance level, and transphobic and anti-Black and anti-Indigenous in its discourse.

I want to be clear that this is one of many conflicts like this in the arts. This blog post started as an essay for an international publisher. But, somewhere in the process of editing that work, I realized that I don’t want to hurt my previous colleagues the way Balzer hurt me (and profit off of that hurt at that). I don’t want to edit this conflict down to vague, legally parsed statements that might implicate the current editorial community of Canadian Art. I just want to tell the truth, finally. And I’m beginning to realize that art isn’t one toxic workplace – it’s a system of toxic workplaces and peoples. And I don’t want to be a part of this art I have described. I want to be a part of something trans, Indigenous and Black governed, and of the future.

That said, I do want to briefly acknowledge the current editorial staff of Canadian Art. I am of the opinion that Jayne Wilkinson has done more for editorial at Canadian Art as Editor-in-Chief, during a period of austerity, than Balzer ever did during his time. I also want to be clear the Bryne McLaughlin and Wilkinson put their jobs and livelihoods at risk during a very precarious time in the arts to support junior editors in embarking on a work stop to demand that the board of Canadian Art address its institutional racism and inequity. The white editors stood fiercely by editors of colour in this action, as well. After years of poor work conditions, underpayment, human rights violations, and toxic work cultures, the staff of Canadian Art was broken. File that under a white man could never (and did never).

During a meeting with the board and editorial community close to my departure, the board was presented with the possibility of a human rights complaint being filed against the organization, the outgoing Editor-in-Chief, and the outgoing Publisher. Because I am a status Indigenous person, I am protected under international human rights laws against the aforementioned forms of harm in the workplace. There are also several international human rights declarations (such as UNDRIP) that protect my cultural knowledge productions. At the time of the meeting with the Board, they committed to change.

Rother did leave the organization of her own accord. The board has hired an interim Publisher. She is white. I remember being privy to a shortlist for our current Editor-in-Chief position. It was also all white. But the board has still not been transparent about how they will be accountable for the numerous harms they perpetuated against their Indigenous employee and Indigenous communities broadly in Canada (though the staff has been penalized for their actions in various ways). These aforementioned occurrences also coincided with a lack of investigation into previous misconduct at the board level; and several recommendations from the staff to the board that included (but were not limited to) board transparency in governance, a work audit, addressing cultural racism against Indigenous peoples at the board level resulting from internal interests, and meaningful action regarding perceived racism within the business side of the organization. Yet, the board of Canadian Art has yet to divulge publicly how it will be accountable to the occurrences herein.

Deciding to publish this finally was a difficult choice. I have teetered back and forth between options and often landed on keeping quiet and staying the course. Ultimately, I am writing this because I am worried about my previous editorial colleagues at Canadian Art and their wellbeing. As I mentioned before, I have the deepest respect and solidarity with the current editorial community of Canadian Art. And, from the outside, it appears that the organization has done little to address or be accountable to the harms it has perpetuated against its staff.

I especially want the public, funders, partners, and advertisers to know that the staff of Canadian Art went on reduced salaries at the onset of COVID-19. I do not know if these salaries have been raised again. Despite these salary cuts, the staff was expected to work full-time hours to help keep the magazine afloat during uncertain times. Even before the wage cuts, staff worked more hours than they were paid to meet the demands of an archaic four quarter publishing cycle devised at the height of print, that is driving the organization into the ground and is no longer sustainable. This pressure is what led to the work stop.

The board of Canadian Art is not composed of untouchable figures. Cloaked, perhaps, but they are real people who all need to be accountable to the way Canadian Art has continually been mismanaged throughout the years, resulting in a hotbed of toxic workplace cultures and interactions with Indigenous communities in Canada. Canadian Art is not a private gallery or art organization, no matter how hard it tries to run itself as such. Canadian Art is a not-for-profit and a charity with a board that is legally accountable to its audience and employees. Following is the current composition of the Canadian Art board. Notably, the board chairs represent an old guard at Canadian Art that was management for the duration of the events described herein.

Co-Chairs: Debra Campbell and Lee Matheson. Board: Amanda Alvaro, Jessica Bradley, David Franklin, Gabe Gonda, Candice Hopkins, Kevin Johnson, Shanitha Kachan, Tanner Kidd, Elizabeth (Dori) Tunstall, Emmy Lee Wall

The Hyperallergic governance structure is coded and not made publicly accessible, meaning that there is no way to deal with the organization except for its oligarchic head. These are not the politics of ~radical~ independent publishing, no matter what the edgelord diatribes of Art History past might tell you. These are the politics of a nepotistic and highly exploitative art world model for publishing that caters to galleries and white administrators – a far cry from the image that the publication projects.