Over the past 5 years, since conflict in industry emerged around the contentious identity claims that have composed “Indigenous” film and art of the past, the industries that have institutionalized and profited off of Native aesthetics have been hard at work with their re-brands.

One of the first pretendians to fall was a prolifically published trans woman. Funnily, one of the prominent pretendian hunters at the center of that crusade has also had a significant amount of questions from the community she claims, about who she is. I fear this is why she didn’t publicly sign the letter denouncing said figure, only orchestrated it.

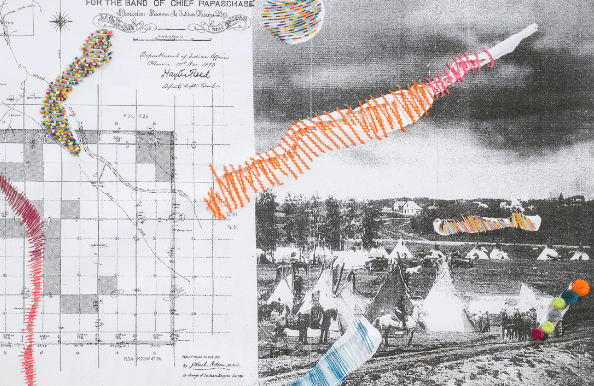

All this, while “Indigenous” art’s ties to zionism for the last decade are being hidden away within “Indigenous” art in favour of a performative, liberal discourse that portrays institutional staff as martyrs for a genocide we have no phenomenology to understand, let alone represent. Some of my current work deals with the development of Indigenous aesthetics in North American art galleries alongside, and in support of, zionist and imperialist interests.

So, I wonder why queer and trans Indigenous peoples – some of us with strong connections to our communities, and racialized peoples – are so surveilled, harassed, and shamed in “Indigenous” industry when these conflicts come to a head. I’m inspired by the work of creators like Kairyn Potts who have used their social media metrics to analyze systemic bias in Indigenous industry and communities; and think it represents some of the most thought provoking Indigenous digital humanities research inside or outside academia. Similar to Potts’ findings, I’ve written essays that point to transphobia, homophobia, and ciscentrism, alongside white supremacy, as causal of bias against queer and trans Indigenous peoples in industry (and community, but that is not what I am discussing herein).

I’m now seeing community based narratives borrowed by “Indigenous” institutions to fund their re-brands. Somehow, for me, this practice feels most charged in the prairies, where many significant “Indigenous” arts and culture leaders from the 2000s and 2010s have faced scrutiny about their identity claims, renounced their identity claims, or simply slipped away from the spotlight. Perhaps it feels so charged because the appropriation of kinship aesthetics to bolster unclear identity claims will now forever be associated with this moment and place. Further, the prairies are a place where “Indigenous” art organizations like Ociciwan, or galleries like the Remai Modern and the Winnipeg Art Gallery, are displacing low-income Indigenous peoples and perpetuating the quick gentrification of the neighbourhoods where they reside. Notably, at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, an Indigenous gallery was erected by someone we now know has potentially committed identity fraud, to represent an Indigenous community that is not of those territories.

I have to wonder if these organizations really know what it means to work through community-based ethics. It’s troubling to see anti-institutional politics and aesthetics be lifted for the benefit of a few institutional players, with no recognition of the harm done over a decade of Indigenous development in art.

Namely, I’m wondering how “Indigenous” art organizations will repair the hurt caused by the countless pretendian collaborators, artists, mentors, and mentees they have supported for decades. How will they repair the curation of a canon of pretendians? If queer and trans, racialized Native youth have had to heal community complaint publicly, why are these institutions that claim community status not offering healing, too?

Specifically, I’m looking at an older generation of white-coded folks who gatekept, and gatekeep, this industry. It’s a disappointing, but not surprising, reality within Indigenous communities that lateral violence is sometimes the strongest form of harm we experience within institutions. I’ve been empowered by a younger generation’s discourse to push up against lateral violence in industry and community. That shame is certainly not mine, or any community member’s, responsibility to hold.

Institutions like Inuit Futures and IIF have not honoured kinship through meaningful healing and connection to those who have been hurt; namely, the students who worked on their projects and in close proximity to Julie Nagam.

But Indigenous art organizations need to honour kinship and the Treaties too, especially as the primary location, outside of institutions, where pretendianism spread within the arts. I’m looking at organizations like Ociciwan, Rosemary Gallery, the Daphne, Forge Project, BACA – I’m sure there are many others I’m forgetting at this moment – to be transparent with communities. There were missteps. There was hurt, and without any transparency about the healing actions taken. Communities deserve public transparency and spaces for healing before more arts development on their territories and backs.

What of the pretendians you have kept, and still keep? Perhaps it’s time that we expand settler-colonial “moves to innocence,” to reflect on the ways that race and colonialism manifest through capitalist relationships between “Indigenous” peoples? At some point, we have to clean up our own yards, too. Because black and white thinking and colonial projection just ain’t where my Peoples live. Those who know, know.

Institutions and organizations need to honour the Treaties through meaningful connections to host communities, not re-branding.