Your art will live on. A call across time and space. Honour the sacredness of how we remind one another that we existed across time.

— Maria Buffalo, as read by Jessie Loyer in nanekawâsis (2024)

There are empty spaces that must be respected—those often long periods when a person can’t see the pictures or find the words and needs to be left alone.

— Tove Jansson, Fair Play (1989)

indian is an idea / some people have / of themselves

dyke is an idea some women / have of themselves— Some Like Indians Endure, Paula Gunn Allen (1988)

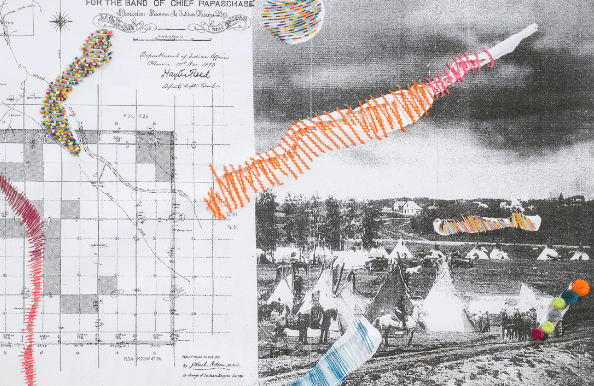

Métis filmmaker Conor McNally has been meticulously working on his documentary feature debut nanekawâsis—about the life and work of Cree painter George Littlechild—for years. Despite being a widely respected Plains Cree artist for decades, I was surprised to learn that Littlechild’s work has not been collected by the National Gallery of Canada, and that he doesn’t have a Wikipedia page. At this pivotal moment in Littlechild’s long and storied career, McNally’s film plays a crucial role in commemorating Littlechild’s legacy. With its focus on the relationships that shape Littlechild’s work—such as his longtime love for his partner—nanekawâsis tells a story of enduring queer love in an Indigenous apocalypse.

Queer love in the apocalypse has become a literary and visual trope in recent years. Amid apocalyptic realities—such as widespread disease and environmental crises—conservative social policies targeting 2LGBTQ+ people have started to permeate everyday discourse. Representations of queer love “at the end” have emerged in response.

At first glance, these representations might seem like expressions of endurance: We’re here, we’re queer, in any mode or reality known on Earth, and to queered peoples. Yet, fetishistic themes of disability and death mar these narratives, hindering any possibility of queer futurity (however ironic such a proposal may be). Amidst a sea of narratives exploring queer deviance and death, nanekawâsis stands out as a realized future, and a remarkable and unexpected memorialization of minor histories and quiet archives.

Read full column here.